This is an old blog that is no longer updated. If you want to read fun stuff about Dutch in English, head over to my Substack. You don’t have to sign up to read it!

Blog

-

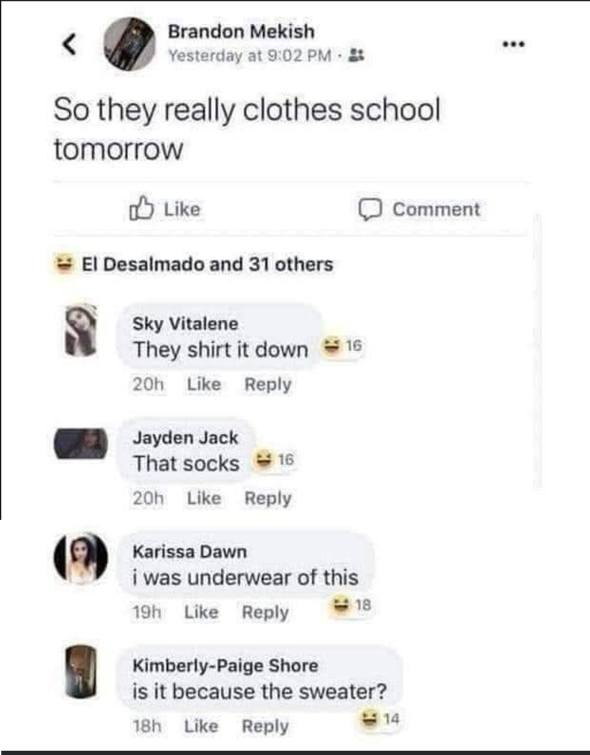

All the ways to use “shit” in English

This fun meme did the rounds a few years ago:

Here are the definitions from Wiktionary and an example sentence for each:

apeshit: “Out of control due to anger or excitement”

I told him the bad news, and he went apeshit.

batshit: “Too irrational to be dealt with sanely”Don’t take any courses from that professor. She’s completely batshit.

bullshit: “False or exaggerated statements made to impress and deceive the listener rather than inform”Don’t pay any attention to him. He talks a lot of bullshit.

chickenshit: “Petty and contemptible; contemptibly unimportant”; “a coward”I told him I wasn’t having his insults, and he just backed right down. What a chickenshit.

My dogshit bike broke again.

horseshit: “Serious harassment or abuse”; “Blatant nonsense, more likely stemming from ignorance than any intent to deceive”He thinks vinegar is alkaline? Don’t you realize that’s horseshit?

Heddwen Newton is an English teacher and a translator from Dutch into English. She has two email newsletters:

English and the Dutch, for Dutch speakers looking to improve their English, but also for near-native speakers who write, translate into, or teach English.

English in Progress keeps English speakers up to date on the latest developments in the English language. Subscribers are mostly academics, English teachers, translators and writers. -

My collection of proof that “clothes” rhymes with “nose”

I’m not sure why it is, and I am worried that Dutch secondary school English teachers are to blame, but lots of Dutch people completely mispronounce the word “clothes”. They say something like “clothe-ese”.

Though one of the main principles of this blog is that having a Dutch accent is okay, in this case this pronunciation doesn’t work because it will lead to misunderstandings.

Also, the solution is so easy: “clothes” rhymes with “nose”. Don’t believe me? Listen to Avril Lavigne

“All of her friends, they stuck up their nose, they had a problem with his baggy clothes.”

Or look at this Simpsons quote:

Or click through these 25372 videos on YouGlish. (Don’t worry, just clicking through the first ten or so is fine.)

Or look at this meme:

But I asked a native speaker and they said it was “cloath-zzzz”

If you ask a native speaker about their language, they are going to want to be helpful and tell you what they feel is the “correct” pronunciation. So they’ll think about the spelling and pronounce it slowly for you, and then they will indeed end up pronouncing the “th” in the middle (as a voiced th, by the way, as in “them”).

But when native speakers are just talking and not thinking about it, they’ll say “I bought some new close.” I promise. Unfortunately, most people don’t realise how they actually talk, so if you ask them they might insist that they always pronounce the “th”. People are funny that way.

Heddwen Newton is an English teacher and a translator from Dutch into English. She thinks about languages way too much, for example about how strange it is that these little blurb things are written in the third person.

Heddwen has two children, two passports, two smartphones, two arms, two legs, and two email newsletters.

English and the Dutch examines all the ways Dutch speakers interact with the English language. It has more than 1100 subscribers and is growing every day. Sign up here.

English in Progress is about how the English language is evolving and how it is spoken around the world. It has more than 1700 subscribers and is growing every day. Sign up here.

-

More coming soon. Ish.

I started this website as an English counterpart to www.hoezegjeinhetEngels.nl, for articles that wanted to be written in English rather than in Dutch.

But then I started writing those articles on Substack instead.

Now poor English and the Dutch is just sitting here, twiddling its thumbs, waiting for me to give it some attention.

But you found it, so that’s something! Now please go visit one of those links I just gave you because you really don’t want to be hanging around here.

-

Forget boats. Here’s the new source of Dutch words in English

While reading the quarterly update of new words added to that behemoth of English dictionaries, the OED, I was surprised to find not one but two words taken from the Dutch. Both of them even got a special mention in the OED blog.

English has a few Dutch words, of course, often to do with maritime pursuits, owing to the time when the Dutch were very good at boats. There’s “yacht” (jacht), “freight” (vracht), “deck” (dek), “avast” (houd vast), “skipper” (schipper), and plenty more.

But now it’s football, it would seem. The words that caught my eye were:

Cruyff turn – The OED definition is “a manoeuvre used by one player to evade another, in which the player with the ball feints a pass while facing in one direction before immediately dragging the ball behind and across his or her standing leg with the other foot, turning, and moving away in the opposite direction.”

Though Johan Cruyff first used this manoeuvre in 1974, it has only now been added to the dictionary.

total football – from our “totaalvoetbal”: “an attacking style of football in which every outfield player is able to play in any position as required during the course of a game, to allow fluid movement around the pitch while retaining the team’s overall structure as players exchange positions and fill spaces left by others.”

Again, the entry notes that this style of football has been practised by Ajax since the 70s, but it would seem the term is now being mentioned in English-language media often enough to warrant an entry in the OED.

As a non-lover of football, I can’t say I’m super excited. But then I don’t know much about sailing, either. Here’s hoping the next batch of Dutch words to go to English will have to do with, I don’t know, chocolate. Or linguistics. A girl can hope!

Read more

-

“I wish you strength” is kind of good English, but not quite…

This article is about how I polled native speakers to find out how weird they find the term “I wish you strength”. If you are here looking for the best English translation for “sterkte”, including some example texts, you should go here.

“Hey, strength!”

In the Netherlands, we have one go-to phrase that we use if another person is in, or will soon be in, a difficult situation. It can be condensed down to just one word: “Sterkte!” Strength.

If someone close to you is ill, dying or dead, if you are ill or dying, if you are depressed about being single, depressed about not being single, if you have a new job, if you have a presentation or if you dropped your mother’s favourite vase and are going to have to tell her about it, if you are sick of your boss but have to go in to work again on Monday, if you have to spend a whole day with your boring in-laws, if you have to eat your best friends terrible cooking…

If there is anything happening in your life that you have to deal with, and it’s not happy, then the Dutch wish each other sterkte. If they are feeling especially generous, they might say Hee, sterkte ermee, he? (“Hey, strength with that thing, yeah?”)

So is it just “I wish you strength”?

I don’t know if it is my British English or if it is the fact that it just sounded too Dutch to me, but saying “I wish you strength” in English always sounded off to me. I even worried that perhaps people would feel the well-wisher was implying that they are not a strong person.

On the other hand, I wasn’t sure, so I decided to crowdsource some language knowledge. I wanted to know if the phrase would sound “foreign” to a native English speaker, if it is a phrase that a native speaker would use. So I put up a questionnaire on Reddit, and asked the following question:

If you were going through a difficult period in your life, for example a death or serious illness in the family, and I sent you a card on which I wrote “I wish you strength”, how would you feel about that?

With the answer options:

That’s nice, and it’s good English

That’s nice, but it’s not good English

Are you saying I’m not a strong person?

Other:

I expected my survey to be filled in by 20, maybe 30 people, so I didn’t pay a lot of attention to making it perfect. In the event, though, it was filled in by almost 2000 (!) people. The age skewed young (because Reddit!).

Results

Here are the results:

Clearly, I was completely off the mark thinking that people might feel that the strength wisher is insinuating they are not a strong person, with only 2% agreeing with me.

There was a reasonable 22% that agreed with me that it sounded “off” (“it’s not good English”), but lots of people responded that they felt the English was fine.

However, the survey was not well-worded, so these results should be taken with about a kilo of salt. I should have asked something like “is this something you would say?” or “If someone is going through a tough time, what would you say or write to them?”

The open responses are the most interesting

I might be a lousy survey-maker, luckily a lot of my respondents were kind enough to write some extra words. It is those extra remarks that are most interesting for Dutch people, I think.

You can really see how mixed the responses are. However, if you scan through them, I think you will agree with me that the best course of action for Dutch people is to steer away from “I wish you strength”.

The remarks English-speakers made at the end of the survey

If someone wished me strength in a letter I would think it unusual and it would depend on the sender, but I might think that they’ve spent time on this letter choosing words carefully, and that in such a sense strength is a good word. It can suggest their support whilst implying that you are capable yourself of succeeding.

Wishing someone strength is idiomatic English, but not formal English. It is something you might hear someone say, but generally would not see written down.

I think it’s common for English folks to wish one another strength.

For “I wish you strength”; as a native English speaker I would consider it “good English” but would assume that the person does not speak English as a first language or heard the saying from someone who doesn’t speak it as a first language. It sounds a bit foreign in a way I just can’t describe. Normally, I think “I hope you can stay strong” or something similar would be used.

“I wish you strength” sounds perfect but is more suited for someone about to go through a hard time rather than someone who has just been through one. Probably a better translation would be “stay strong.”

I think wishing someone strength in trying times is fine if you follow it up wtih something. For example: “I wish you find strength to perservere in these trying times. I will be here to help you find that strength should you need it.” With no other context it would do nothing but confuse/insult the recipient of the sentiment and even with the context it could still come off as odd.

Wishing people strength is definitely something that happens in English.

I think saying you wish someone strength is a normal expression in hard times, at least in the US.

Wishing each other strength isn’t a common thing to do in English, but grammatically it’s perfectly fine.

“I wish you strength” makes perfect sense and is good English, but may sound somewhat religious or New Age-y. It seems to be a more popular phrase in the Wellness community in the USA for instance

“On the “wish you strength” question, I said “nice but not good English”. I couldn’t answer “good English” because you made me think about it, but if I got such a card I would not notice the slightly improper English.

In the suburban / semi-rural midwest US, it wouldn’t be out of the ordinary to hear “wishing you strength and comfort in this difficult time”. I didn’t find that phrasing of at all.

The strength phrase may vary in understanding based on how religious or mystical the listener is. But the phrase “give me strength” is known and used widely.

“I wish you strength” sounds very much like something I would hear at my (very non-traditional) synagogue — they often translate Hebrew in ways that feel like this, both unusual sounding due to the directness of the translation and also surprisingly poetic and powerful.

Generally phrases like “I wish you strength” are followed up with some context, like “I wish you strength in this trying time”.

I think “I wish you strength” makes total Sense in English, it’s just not super common to hear but I have heard it.

I’m super interested in the topic as I’m learning Dutch as a second language and funnily enough, immediately recognized it was relating to Dutch when you mentioned “strength”.

I thought “I wish you strength” was unusual but sweet.

I don’t wish “strength” for others, but I do tell some people to “stay strong”.

Open responses to the question

These people are responding to the question “If you were going through a difficult period in your life, for example a death or serious illness in the family, and I sent you a card on which I wrote “I wish you strength”, how would you feel about that?“

I appreciate it, and it’s good English; but I absolutely would not use it myself if I were sending a card, because yes, I worry that the recipient can interpret it as saying they aren’t strong.

It’s good English, but maybe a bit archaic

It’s nice and it’s dated English

The sentiment is nice, but it could be misinterpreted and isn’t something someone would often say in English.

Doesn’t feel right, but it’s good English

That’s nice, and it’s good English, but it feels foreign if someone said that to an American

it’s good English but it’s trite

I would understand but I would think you are not a native speaker of English

it’s good English grammatically but isn’t a commonly used phrase. It’s weird, not wrong.

It’s become good enough English over the past 20 or so years.

Its a nice sentiment, but I would prefer if it elaborated — like, “I wish you strength to deal with your grief”.

It’s fine English tbh even if it might not make 100% sense

The english is fine, but on it’s own the statement lacks clarity in that situation.

Givrs me the “thoughts and prayers”-vibe. But sounds like good english 🙂

It’s not a common English phrase but it isn’t necessarily bad, and I would appreciate it.

as a linguist i’m having a hard time with this survey saying “good” and “bad” English, i would say it makes sense as it’s meaning is understanable

Fine english, but overly trite and a little demeaning.

That’s nice and it’s grammatically correct but doesn’t flow well

It seems like the classic “just be positive!” mindsets that ultimately ignore the true struggles and feelings of the person; nothing matters except to be mentally strong.

I get the jist, but it isn’t a common turn of phrase

That’s cheesy but fine enough English

That’s some empty platitudes, but fine English

It’s fine, but sounds kinda dated/archaic

It’s fine, it’s just a weird thing to say.

The english is fine, it’s an unusual thing to say unless you are very religious

That’s nice; English is malleable enough that, while it’s not PROPER English, it’s still fine.

It’s good English, but it feels awkward

Nice, but abnormal. Not necessarily bad English, but maybe from a different culture.

That’s nice, good English but uncommon.

it’s fine English, but a little rude

That’s nice, fine English, little unusual though

I dislike the sentiment, but I think it’s ok English

This might be more appropriate to say to someone going through a challenging endeavor that ultimately is their responsibility. Saying it to someone who is going through a hard time might come off as distant and unsupportive (ie. “I can’t do anything for you but I wish you strength to get through it.”) I’d avoid using this phrase in those situations.

I wouldn’t say it’s poor english, necessarily, but it’s definitely unusually worded

It’s good English but a cliché sentiment.

I would think Buddha or Asian culture

I understand the sentiment, but the wording is awkward enough that I could see it being used as backhanded in some petty instances. Awkward word choice.

That’s nice, but you’re either toxicly positive or haven’t ever dealt with a close death yourself. -

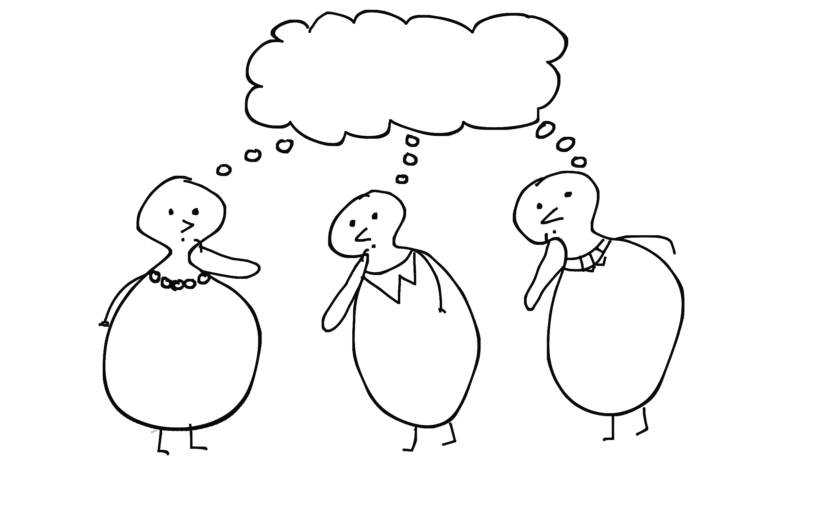

Is “to think along with” a good translation for “meedenken”?

What is “meedenken”?

The Netherlands is famously a culture of teamwork and compromise, and as such the word “meedenken” is one that is often used. When one person asks another “kun je even met me meedenken?” (literally: Can you ‘think with me’ for a moment?), what they want to do is explain a problem they are having to the other person, and then brainstorm possible solutions together.

Translating “meedenken”

In recent years, I have noticed that translators (both human and AI) are choosing to translate the word “meedenken” as “to think along with”. So the question above would be translated as “Can you think along with me for a moment?”.

I grew up speaking both Dutch and English, and sometimes that leads to problems as a translator, because English phrases and Dutch phrases get mixed up in my brain. When it comes to “think along with” I was unsure of two things: is it actually a phrase that people would understand, or would it just confuse them? And if yes, does it actually mean the same thing as “meedenken”?

There are two schools of thought when it comes to questions like this. One school of thought (prescriptive, for the linguists among us) says that you should look it up in a dictionary or ask a specialist. The other one (descriptive) says you should find out how real people speak and understand this phrase. I am firmly in the second camp. So I put out a survey on Reddit.

Results

I got 584 responses from people who were older than 21, and did not speak Dutch or German (leaving those in would have contaminated the results).

First, I asked:

Here are the responses:

So there is quite a big group (62.4%) who are of the opinion that the phrase “is not good English”.

Then I asked:

Here are the responses to that one:

When a Dutch person uses the phrase “please think along with me”, they are asking their conversation partner to brainstorm on a problem with them. These results suggest that that is not how they would be understood.

(The 5 people who replied “other” all said that they thought it was a combination of the two most popular answers. )

Some extra remarks people made

In my survey I gave people a chance to add remarks at the end if they had any. Here are some remarks people had about “to think along with”:

When I hear “think along with me”, it sounds like something an elementary school teacher (of ages 5-7) might say to their students, not something that adults would use with each other.

I would use “put our heads together,” a common phrase for that. Doing anything “along with” someone implies that they’re the expert and you’re keeping up, like “cooking along with” might mean watching a video while you try to make the same dish.

The “along with me” construction in English implies that the speaker is leading and the other person is being invited to follow; I would not expect a collaboration.

Conclusion: “to think along with” is not a good translation for “meedenken”

The term “meedenken” is used very often in Dutch to mean brainstorming a solution to a problem together. Many people translate this with “to think along with”, but when a Dutch person asks “Could you think along with me?” they are very likely to be misunderstood, as the majority of non-Dutch people over the age of 21 feel that this would mean that the Dutch person wants them to follow their train of thought, to listen to them while they explain their reasoning.

Is this a huge breakdown in communication? Probably not, the meanings are very similar, and when two people are talking together and one of them uses this phrase, it will probably sort itself out.

When a Dutch person is speaking, they would do well to say something like “Do you have a minute to brainstorm solutions for this problem I am having?” or “Can I pick your brain for a second?”

More importantly, when a translator (such as myself) is translating a Dutch text into English, “meedenken” should NOT be translated as “to think along with”.

So how SHOULD I translate “meedenken”?

I talk about that at length on my Dutch site hoezegjeinhetEngels.nl, where I try to find good translations for difficult-to-translate words. I’m not 100% happy with any of my translations for “meedenken”.

Ideas that I have come up with include “to bounce ideas off a person”, “to brainstorm solutions”, “to put your heads together”. You can read them all here.

Dutch companies love saying “we denken graag met u mee!” which I find especially tricky. Do you have any good ideas for a translation? Let me know in the comments!

Stuff I should have done better

A number of people disapproved of the fact that I asked people if something was “good English” or not. They felt I should have written something like “it is not natural-sounding English”. The reason I asked the question the way I did was because 1) I wanted to keep things simple and 2) I am interested in how Dutch people would be perceived if they were interacting with English speakers. I felt the perception of “is it good English” was more important than “is it natural English”. But it’s all open to debate 😉

There were 4 people who noted that I had written down the answer options incorrectly, and their answer would have been “I want you to follow my train of thought, to listen to me while I explain my reasoning”. They were, of course, completely correct – my answer options did not fit my question properly. Luckily it appears most people weren’t phased by my own bad English.

Choosing which responses to include

I got a whopping 1990 (!!) responses. (This is the power of Reddit. I highly recommend it to any university student trying to get responses for their thesis.)

To my regret, I had to take away 830 responses for this particular question, because I had made an important omission in my answer options, and the responses via Reddit were so fast that by the time I had noticed and rectified it, all those people had already started filling in the survey. (Lesson learned: always do a pilot survey with just a few participants, so you can pick up on omissions!)

Of those left, I had to remove 126 people who had not filled in the whole survey. I also took away everybody under the age of 21 (a whopping 375 people; see here the downside of doing research via Reddit), because I wanted the answers to reflect the kinds of people that might potentially do business with Dutch people. Then I took away everybody who spoke Dutch, German or Afrikaans (71 people), because I wanted to know what people thought who had never heard the term “meedenken” (or the very similar German “mitdenken”).

-

John Oliver does a Dutch accent (and we learn “Basilius” sounds like a typical Dutch name)

I wasn’t quite ready to start publishing on this website, but then I saw John Oliver’s Last Week Tonight episode on carbon offsets, and I thought: “well, there’s my first post.”

In the episode, Oliver ponders the term “ten dollars to offset your pig”. An then comes this bit:

“Ten dollars to offset your pig” sounds like a Dutch sex act that was sent back and forth through Google Translate one too many times.

He then puts on a strong, fake Dutch accent to impersonate what I assume is meant to be a Dutch pimp, and says:

“For ten dollars, Basilius, he offset your pig. So good, so strong, your eyes will pop, and your brave testicles will switch (twitch?). So are we doing this? Basilius! Offset that pig!”

Find the clip at the 7 minutes 47 seconds mark:

John Oliver is a hero

Okay, first off, John Oliver is amazing, and I’d totally marry him if I weren’t happy with my partner, and he weren’t happily married, and we would meet somehow on an airplane or something, and he’d be romantically interested in me, for the long term, not just a fling. By making serious issues funny, he is educating the world and probably having more positive effects on it than 1000 policy makers.

That having been said, let’s talk about the Dutchness:

Where he got the Dutchness right

Saying “he offset your pig” instead of “he will offset your pig” – this is an absolutely correct example of grammar from Dutch English speakers. When I’m proofreading English texts written by Dutch people, I sometimes feel adding “will” to future actions is, like, 80% of what I do.

Put in present tense, there should of course have been an “s” after “offset”; “he offsets your pig”. Most Dutch people wouldn’t do this wrong anymore, because it is drilled into them so thoroughly at school, but it is certainly a mistake that is made.

Saying “dis” instead of “this” – yep, that’s what they do. It’s something I plan to write about more in future, but I actually think using a “d” sound for the voiced “th” (like in “this”, “that” and “though”) is quite a charming part of the Dutch accent.

Saying “so strong” – Dutch people overuse the word “strong”, not because its literal translation “sterk” is such a much-used word in Dutch, but because they don’t know how to translate words like “krachtig”, “heftig”, “hevig”, “flink”, “fors”. They know “strong” isn’t the right word, but it’s the best one they can find in their mental English lexicon, and they know the listener will interpret it the right way, so they use it.

Where he got the Dutchness – kinda right?

Pronouncing “s” like “sh” – Okay, so this is a little bit true, but far too overdone.

The Dutch “s” is more forceful than the English one – the Dutch keep their tongue flatter than the English when making an “s”, meaning the air is pressed past more of the tongue. To Dutch people, this doesn’t sound like a “sh” at all, but to English people, who make the “s” with the tip of their tongue only, anything that uses more tongue than that sounds like a “sh”. When they copy a Dutch accent, that is often the feature that they choose.

It is my personal observation that Dutch people of a younger generation are far better at pronouncing the “s” in a more native English way, and it is the older Dutch that have that “sh”- way of speaking. And even for that older generation, I don’t think it is a fair portrayal of their accent to make the “sh” as pronounced as Oliver is doing. But he’s doing it for laughs, he needs a quick and dirty way to make it clear he is pretending to be Dutch, and the sh-thing is, for English speakers, a quick marker for the Dutch. So I get it.

This video from a Dutch comedian with a knack for accents goes over five ways to “do a Dutch accent” and you will notice the “s”- “sh” thing is not one of them. It just goes to prove my point that this marker is something from the past.

Something that sounds like a weird sex act gets connected to the Dutch – Oh well. I prefer this prejudice to anything to do with weed and drugs. Being open-minded about sex and allowing people to communicate freely about this topic means this little country has reduced a lot of problems that other countries still face.

Where he got the Dutchness wrong

Calling the prostitute “Basilius” – I have NO IDEA where this comes from, and if anyone reading this knows, please leave a comment! I can only think it’s a contraction of “Basil” (not a Dutch name in the slightest) and “Cornelius” (a very outdated Dutch name). I guess they wanted a Dutch-sounding name with two “s”-es so they could use it for the “sh”-joke, and “Basilius” sounds Dutch to Americans???

“Your brave testicles” – Dutch people do misuse the word “brave”, thinking it means “obedient”, but they would not use it in this sentence.

“Dollars” – obviously, if you travel to the red-light district in Amsterdam hoping to offset your pig, you will be paying in Euros, not dollars.

Heddwen Newton is an English teacher and a translator from Dutch into English. She has two email newsletters:

English and the Dutch, for Dutch speakers looking to improve their English, but also for near-native speakers who write, translate into, or teach English.

English in Progress keeps English speakers up to date on the latest developments in the English language. Subscribers are mostly academics, English teachers, translators and writers.